Figure 1: artwork from Michele Horrigan. Picture derived from www.michelehorrigan.com.

© Michele Horrigan

Guestblog by Isabelle Duval

Stigma Damages

On March 20, 2025, Irish artist Michele Horrigan gave an insightful lecture at Tilburg University titled "When Art meets Environmental Justice." In her presentation, Horrigan particularly discussed Stigma Damages, an ongoing arts-based research project she has been working on for over a decade. At the crossroads of artistic research and activism, Horrigan has been investigating the lasting environmental and social impacts of Aughinish Alumina, Europe's largest bauxite refinery, since 2011. Situated near Limerick, her hometown along Ireland's Shannon Estuary, the refinery was established forty years ago by Canadian interests and is now owned by Rusal, a Russian company with well-documented connections to Vladimir Putin’s war efforts.

In this context, the term “stigma damages” is to be understood far beyond its traditional legal definition of property devaluation. While the inhabitants of Limerick have undeniably witnessed the value of their homes plummet due to the exploitation and pollution of the environment they are living in, the impact of stigma encompasses far more. It symbolizes the profound environmental, social, cultural, psychological and physical scars left behind by environmental injustice. The damage is not only financial; landscapes are being ravaged, a toxic red dust carried by the wind invades gardens, homes and people’s lungs alike. The air grows increasingly devoid of butterflies and birds, every vibrant sign of life is slowly disappearing. And perhaps most painfully, living under the shadow of an industry that serves the interests of the Russian war industry is a burden that is difficult to bear. The harm inflicted on individuals, communities, and ecosystems is both enduring and immeasurable.

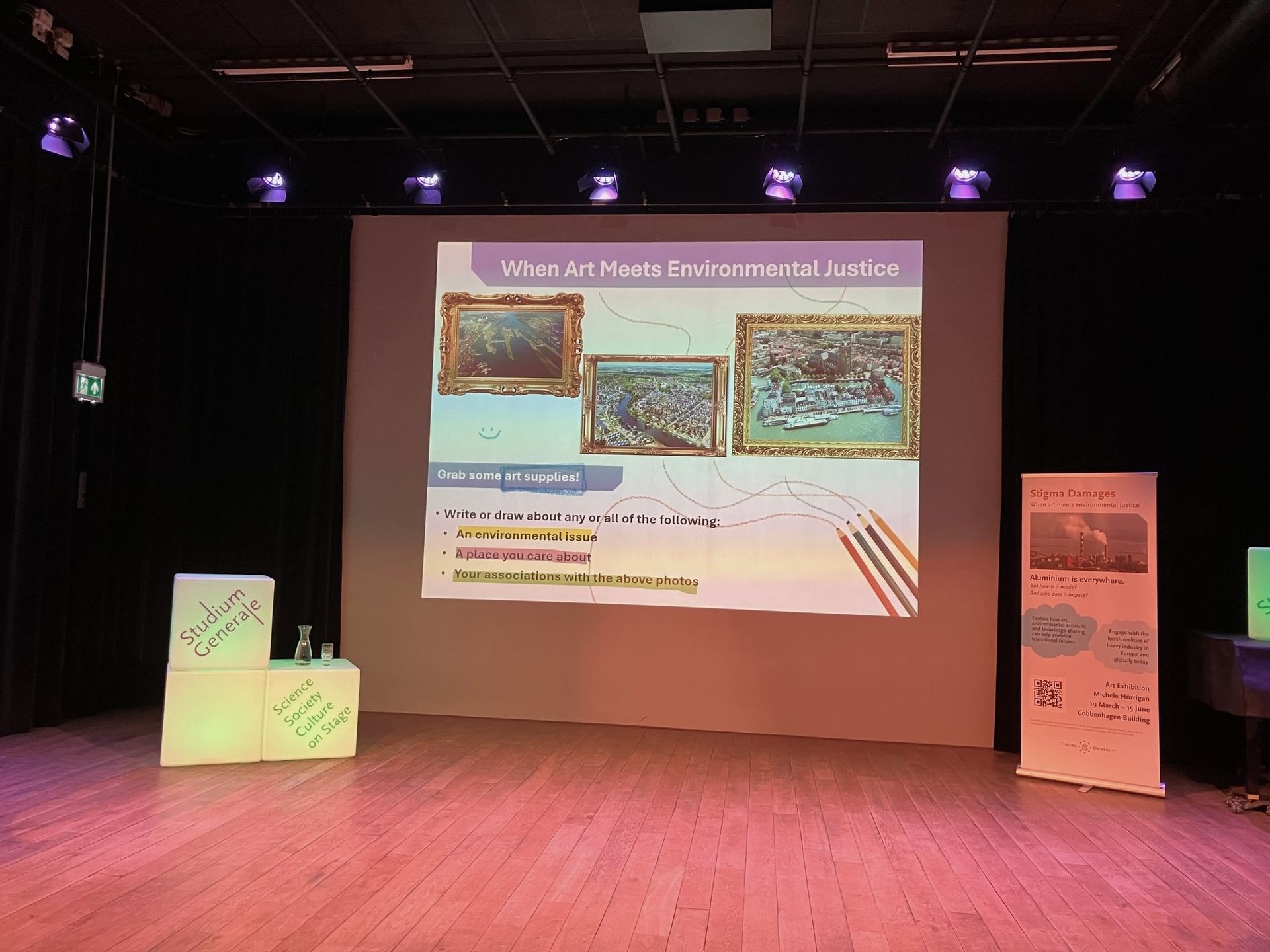

Figure 2: Michele Horrigan delivering her lecture' "When Art meets Environmental Justice" at Tilburg University (March 20, 2025). Picture taken by Caroline Vander Stichele.

Let’s think about our home

Horrigan opened her presentation with powerful images of Dutch cities living under the shadow of polluting industries, facing the same peril as Limerick. She highlighted Ijmuiden and Tata Steel, Groningen with its gas extraction, and Dordrecht, where Chemours fabricates polymers—each city grappling with environmental harm and the enduring consequences of industrial exploitation.

To shed light on the pollution, biodiversity loss and health issues resulting from the Aughinish Alumina refinery's operations, Horrigan uses a variety of artistic methods and mediums, such as archives, audiovisual installations and found objects. She describes her work as an attempt to “make sense” of the environment in which she lives - an area where nature is, as she puts it, being “raped” for the benefit of the aluminium industry. When asked what she understands by the term "environment," Horrigan cites the slogan of the Environmental Justice movement: "the environment is where we live, work, and play."[1]In this regard, her need to “make sense” deeply resonates with Emanuele Coccia’s Philosophy of the Home, which posits that home might hold the answer to our salvation in the face of today’s multifaceted crisis. In his latest book Philosophy of the Home: Domestic Spaces and Happiness, Coccia demonstrates how our living spaces are far more permeable than we realize, urging us to move beyond the problematic inside/outside and public/private dichotomies.[2]

“Aluminium is everywhere”, Horrigan stresses – it can be found in our phones, our homes, even in our bodies. Its presence, and that of the remnants of its manufacturing, can be traced even within us, as confirmed by a test she conducted on the presence of heavy metals in her own body. Coccia argues that the home is no longer a confined, isolated space, and Horrigan illustrates how its boundaries are blurring; the red dust from the processing of the bauxite that is shipped all the way from Guinea, has infiltrated not only Limerick and its surroundings, but also her home and her body. In our global society, our homes have become, to paraphrase Coccia, "portable spaces devoid of geographical anchoring." As Coccia aptly states, "the home has become a planet," and vice versa. In the era of globalisation and climate change, one cannot be a truly engaged citizen while remaining behind closed doors. Like Coccia, Horrigan calls us to think about the notion of home, urging us to reconsider its role in shaping our collective imaginary, and its potential to help us act toward a more equitable and sustainable way of inhabiting the world. Through her art, which underscores the lasting and damaging effects of the Aughinish Alumina refinery on nature, communities and individuals, Horrigan forces us to rethink the very concept of home - her home, our home, and its profound significance in an interconnected world.

Figure 3: Presentation of Michele Horrigan's artwork in her lecture "When Art meets Environmental Justice" at Tilburg University (March 20, 2025). Picture taken by Caroline Vander Stichele.

Art as a platform for dialogue and a call to action

Horrigan emphasizes that through her work, she aims to transform complex environmental issues into accessible and thought-provoking art that both challenges and engages the viewer. Rooted in the tradition of ecological art, her creations are haunted by the question of awareness surrounding the environmental and societal challenges we face. By archiving the communication strategy employed by the refinery’s management – ranging from advertisements to the creation of a butterfly sanctuary (though there are no longer butterflies spotted in the area) and a trail running around the refinery - she deconstructs the visual narrative crafted by the industry to portray itself as a benevolent force,not only for the local community but also for nature. In this sense, Horrigan’s work not only confronts her public with the local and global longlasting implications of unchecked industrial activity, she also sparks important conversations, exemplifying how art can address urgent political, industrial, and environmental concerns. During her presentation, she underscored the importance of art existing beyond the confines of the art world if it is to have any meaningful impact and inspire positive action toward environmental justice. To illustrate this, she played a video recording the heated discussion that followed the screening of her film about nature surrounding the Aughinish Alumina refinery at a local community center. What truly matters is thus not just “when art meets environmental justice”, but also where it takes place, and who it engages.

Where religion meets Horrigan’s art

At first glance, Michele Horrigan’s art may seem far removed from any notion of religion. Yet, viewing our planet as the shared home of all beings (humans and non-humans alike), and acknowledging its suffering, profoundly echoes the message of Pope Francis' 2015 encyclical letter Laudato Si': On Care for our Common home.[3] While Horrigan’s work may not explicitly align with religious themes, it is easy to identify potential connections between Horrigan’s art and religious thought. To paraphrase Novotny, our environment is not only where we live, work, and play, but also where we pray. Another key aspect to consider is that Horiggan’s work is a striking example of what French art critic Nicolas Bourriaud refers to as relational art or relational aesthetics.[4] This approach in art practice sees artists acting more as facilitators than makers, with art becoming a medium for exchanging information between the artist and the audience. Here, the artist empowers the public by providing them with the knowledge and tools necessary to actively engage in transforming the world.

Another central aspect of Horrigan’s mission is to expose the harmful connections between aesthetics, economics, and politics, while criticizing the coercive ideology behind the “dillusion” conveyed by neoliberal aesthetics. At the same time, she seeks to reframe environmental justice outside the dominant visual regime that those advocating for climate action must confront and challenge. By exploring the dual etymology of the word "religion" - as both "re-legare" (to connect) and "re-legere" (to reread) - one could argue that religion’s role in times of climate crisis is to foster connection and offer new interpretations of our predicament. As religions scholar Birgit Meyer observes, religion is an “aesthetic formation” built upon shared communal imagery and imaginary.[5] In this way, like art, religion holds significant potential to advocate for change, broadening our understanding of today’s complex crisis and inspiring us to envision a narrative that respects both human and nonhuman life alike.

Grounded in ethical principles, Stigma Damages is a work of art that shows, in an epoch where we know more than we truly understand, the power of art to shift our perspective. By offering access to alternative knowledge, art can highlight the interconnectedness between human experience and the environment, and challenge us to acknowledge the urgent need to care for the broader ecological and social systems that we inhabit as our common home. Delving into the environmental challenges posed by heavy industries like Aughinish Alumina, Horrigan strives to help local communities better comprehend the threats they face, and provide them with the tools to combat the environmental harm they are exposed to. She invites the viewers to reassess their relationship with the materials that permeate their daily lives, drawing attention to environmental injustices and igniting indignation. Yet, her work is not merely a critique – it is a call to action. Horrigan urges us to move past passive observation and become active participants in fostering a more equitable and sustainable stewardship of the Earth. Environmental injustice is pervasive, and we can no longer afford to look away.

Bibliography

[1] Novotny, Patrick. 2000. Where we live, work, and play : the environmental justice movement and the struggle for a new environmentalism. Westport, Conn.: Praeger.

[2] Coccia, Emanuele. 2024. Philosophy of the Home: Domestic Spaces and Happiness. London: Penguin Books.

[3] https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/encyclicals/documents/papa-francesco_20150524_enciclica-laudato-si.html

[4] Bourriaud, Nicolas. 1988. Relational Aesthetics:. Paris: Les Presses du Réel.

[5] Meyer, Birgit. 2015. Aesthetic Formation: Media, Religion and the Senses. London, New York: Palgrave MacMilland Ltd.

Environmental injustice: “artivist” Michele Horrigan strikes back